For me, Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, is all about traditions — creating them and recalling them. And for my family, 85% of our traditions happen around the dinner table.

So yes, of course you’ve got to listen to someone blow the Shofar 100 times. AND, yes, you’ve got to throw bread, or nowadays pebbles or seaweed, into a flowing body of water to symbolize the things you wish you hadn’t done this year (a ceremony known as tashlich). But mostly, you spend a lot of time eating, especially sweet things like dipping apples in honey, because the major underlying theme for this celebration is to ensure that you enter the new year with sweetness and hope.

(Eat your apples and honey now as things only get sweeter as we head into Fall, eating dozens of 100 Grand bars as I’m passing out candy to trick-or-treaters or overdoing it with Thanksgiving yams that have been sufficiently marshmallowed).

Here are some of my family’s traditions — and some new ones that are evolving in L.A. as modern chefs take on ancient customs.

Mom’s traditions

My mom was born in Newark, but raised in Pico-Robertson. Her parents, Selma and Vic, moved to the neighborhood less for the synagogues and more for the delis — and the ritzy proximity to Beverly Hills.

My mom’s fondest memories of Rosh Hashanah were at the kid’s table in the early 70s, over the hill in Canoga Park at her Nana and Auntie Jan’s house.

She remembers walking into the smell of Nana’s homemade potato knishes — “like the ones you’d get at Label’s Table — but Nana’s were better.” Once seated, there’d always be mixed nuts on the table — so you could nibble your day’s worth of calories before the meal even appeared.

They’d always have sliced apples dipped into a ramekin of honey, tzimmis(carrots, sweet potatoes, and prunes), noodle kugel and brisket, and my mom remembers her older family members vying for the pupik, the gizzards in the chicken fricassee.

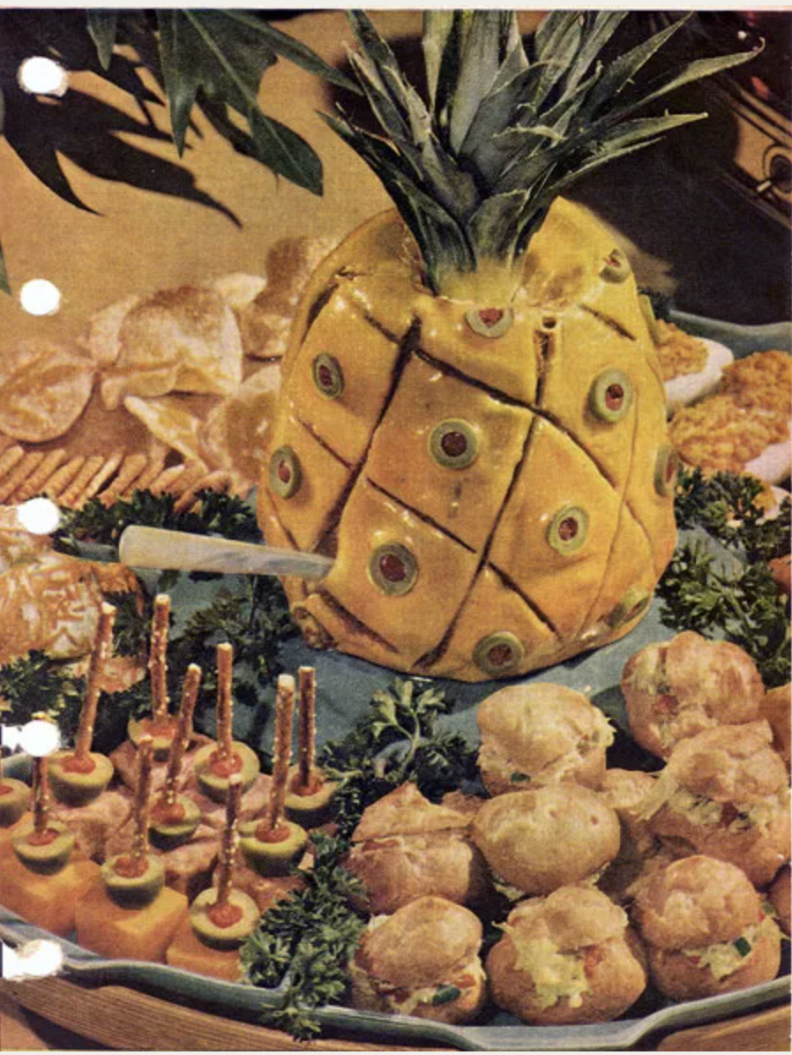

Grandma Selma was “world famous” for making sculptures out of chopped liver. In those days, most Ashkenazi liver dishes came from chicken, but Selma’s recipe called for calves liver, and “everyone would go crazy for it,” according to my mom.

Selma molded her chopped liver into the shape of a pineapple, adding cross hatches and a crown of real fruit fronds, adding pimento green olives to make it look like a real pineapple.

Meanwhile, my mom’s Aunt Jackie was the Queen of the Jello Mold — she’d put fruit cocktails inside of wiggly Jello. My mom remembers telling her sister, “Jello is the only food you can’t spit out if you don’t like.”

Interweaving traditions

Chef Rebecca King is a private chef who owns and operates a culinary concierge business and is the purveyor of a “a very unkosher deli” known as The Bad Jew.

King trained in the kitchen at deli-inspired fine-dining establishment Birdie Gs and learned to use the smoker at Texas-style Flatpoint Barbecue. Over the past seven years at pop-ups around LA, The Bad Jew has developed her treyf take on pastrami with her signature Porkstrami.

Her family told her, “Rebecca, you’re gonna get us in trouble” with the branding for The Bad Jew, but she says it really resonates with people.

As a private chef, King has cooked High Holiday meals for a wide range of family traditions.

“I have clients who keep kosher, who are secular. Some want a traditional Ashkenazi meal, others want more adventure, maybe a Mediterranean or Asian twist,” she said.

Her own family background is Ashkenazi — she grew up in Shaker Heights in Cleveland, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood — and her most potent Rosh Hashanah memories are of her grandma’s matzo ball soup and all of the kids wildly running around her grandparent’s penthouse.

But she says she also enjoys cooking in the Sephardic tradition — “I like flavor, really spicy foods, the herbaceousness — just intense flavors that I love.”

“I’ve done it all… 15 million Rosh Hashanah classics,” she smiles, quoting from Aleeza Ben Shalom in the Netflix series Jewish Matchmaking: “There’s 15 million Jews in the world, and there’s about 15 million ways to be Jewish.”

“There’s no way to do it wrong.”

This Rosh Hashanah, King is excited to serve roasted chicken, tzimmis carrots, and her signature oak-smoked lamb peppered with baharat seasoning topped with coriander leaves, with pomegranate molasses and arils, those juicy pomegranate seeds.

King uses pomegranates because they’re another symbolic fruit for Rosh Hashanah, representing fertility and abundance. (I remember learning that there are supposed to be 613 arils in each fruit, and that’s how many commandments there are in the Torah. Though it’s not an exact science.)

Growing a plant-based tradition

Megan Tucker is the Culinary Institute of America-trained chef behind pop-up Mort & Bettys, a Philly-style plant-based Jewish deli. “Everything is made from scratch — and there’s no fake meat here, it’s all seasonal produce,” Tucker said.

The deli is named after Tucker’s grandparents, Mort and Betty. They were both born to New York City Lithuanian-Jewish families in 1912 — and met at a Borscht Belt summer resort, “like Dirty Dancing but without all the drama,” Tucker said as she laughed.

Mort was an engineer and owned a piano factory that was converted to a wartime airplane factory during the war. Betty had a degree in accounting and worked for the city — and even ran for local city council.

Tucker has infused that old-school Jewish tradition into a modern, vegan approach to Rosh Hashanah dishes. This year’s menu is matzo ball soup, a mushroom paté plate, and her popular brisket made from seared oyster and shiitake mushrooms.

It’s cooked in kosher red wine with tomatoes, onions, nutritional yeast, bay leaves, thyme, garlic, and what Tucker calls “real baby carrots, not the cut kind — carrots are so important to soaking up the flavors in the brisket.”

The sweeter offerings will include symbolically round challah (representing the continuity of the seasons), a chocolate pumpkin babka, and an apple honey cake inspired partly by Amish farm stands in central Pennsylvania.

Pre-orders have already closed for Rosh Hashanah specials, but Tucker will be at the Atwater Farmer’s Market on Sept. 17 with whatever hasn’t sold out.

Traditions for the cooking-avoidant, time-pressed wage slave

I know some of us don’t have family in town — which might make it difficult to access traditional holiday feasts. But it is possible to assemble a quick and easy Rosh Hashanah meal.

(Shoutout to my editor, Gab Chabrán, who knows I’m the King Of The Family Meal Deal.)

Listen, I regularly serve dinner to 4-12 at my dining room table, and I’m always on the lookout for great value take-out offers. So, if you just wanted me to drop an instant Traditional Ashkenazi Rosh Hashanah dinner, I suggest you order a Gelson’s High Holiday Meal package. There are many other places you can order this kind of meal, like smaller delis, but what’s convenient (if you live near a Gelson’s) is that since they are doing supermarket-sized volumes, your food will be ready when you need it.

Nothing beats home-cooked — but sometimes you may have a cadre of tiny cousins running around your home demanding food, and you just need something to give them.

The reason you’re feeding people is to facilitate them to go on with their evenings without thinking about hunger. Well-fed people can laugh and be silly with their families, like bootleg retellings of The Wise Men of Chelm (a Yiddish folk tale) or impromptu vaudeville performances from the kids’ table or dishing out gossip from someone your grandma knew in the old country — all of these happy activities require that we not be starving.

So, for me, my point is: WHAT YOU EAT AT THE ROSH HASHANAH MEAL DOESN’T REALLY MATTER — as long as you can keep your guests happy and well-fed so they can postulate on a sweet new year.

Mix and matching old and new traditions

My mom has finally revealed her menu for our family’s meal. Here’s what we can expect from this year’s celebration:

Milwaukee Brisket from a 1970s Jewish cookbook called Oodles Of Noodles (Green Edition). It calls for a brisket/flour/water/Lipton’s Onion Soup mix, and I guess the Milwaukee-ness comes from the recipe calling for a cup of beer. (This year, my mom will be using a cup of glass bottle Mexican Coke instead, as a Jewish cooking Facebook group just recommended it.)

She will also incorporate silan, a date syrup, into the Pomegranate Silan Chicken she found on Kosher.com — with a jar of the silan that her friend Dorit brought back from Israel.

The pomegranates in my mom and dad’s backyard have not quite been harvested, so she’ll have to get them from Smart & Final. My dad will definitely be into this chicken — but I bet he’d really like that pomegranate lamb from Chef King.

My mom will also be making a couscous with seven vegetables — zucchini, carrots, chickpeas, (and four more for sure!) — because seven is a lucky number, like the seven days it took to create the world. She found this recipe in The Nosher section of My Jewish Learning.com. I hope that it tastes like that epic family-sized tagine we had at Moun of Tunis on Sunset earlier this year.

This story originally appeared at LAist.